- Unpacking Beauty

- Posts

- What does "science-backed" and "clinically proven" beauty even mean? 👩🏻🔬🧪

What does "science-backed" and "clinically proven" beauty even mean? 👩🏻🔬🧪

We're all being duped by science-washing.

Hey - Zahra here 👋.

Here’s your monthly 10-minute read with my no B.S. take on beauty.

If you’ve got any feedback or recommendations on topics you’d like me to deep dive on, feel free to reply to this email.

As always, I’m grateful you’re here. x

In today’s issue:

🧪 Are we being duped by science-washing? Ever wondered what all those science-y terms on your skincare mean? Turns out, it’s not what you think.

👩🏻🔬 Skincare nerd? This book is such a good read.

P.S. If you’ve been forwarded Unpacking Beauty by your bestie (what a star!), you can subscribe here for the next (free) issue.

We’ve all been there.

Falling for terminology like “science-backed” and “clinically proven” on the bottles of our beauty products. This kind of terminology has become so popular today that if a brand doesn’t claim it, we wonder if we’re being duped.

But have you considered that you might be getting duped by science-washing instead?

Beauty brands have been using the aesthetic and language of science for several decades now, all in the hopes of reassuring consumers that their products are nothing short of elite. But with barely any legal regulation around the language, brands often toe a slim-to-none line of misrepresentation, or worse, just straight up lie.

For one, terms like “science-backed” and “clinically proven” literally have no legal meaning. That is, they haven’t been approved for legal use by regulatory authorities like the FDA nor have they been defined as such. Often, brands will use one or more ingredients that have undergone independent clinical trials (usually done by the manufacturer of said ingredient, at specific percentages, and under very specific conditions to document efficacy), add them to their formulations, test them under their own in-house trials, and call it “clinically proven”. Misleading much?

To you and and me, “clinically proven” implies that a product has undergone rigorous, scientifically sound clinical trials comparing the product to a placebo or an industry gold standard in order to prove that this product is highly effective. But in reality, the brand manufacturer has no legal obligations to carry out such in-depth clinical tests.

Metafor Studio

While one would expect that a brand labelling their product as “clinically proven” has trialled the product on volunteers with high quality ‘before and after’ imagery that has been independently verified, this is often not the case.

In India, we use the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 1940 and the Drug and Cosmetic Rules, 1945 to regulate cosmetic products. The Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation of the CDSCO is the main regulatory authority for the cosmetics industry in India. Under these frameworks, any cosmetic product manufactured in India or imported from elsewhere must fall within the definition of a cosmetic product (which is different from a pharmaceutical product), must be shown to be safe for use on skin, that the ingredients have been assessed, and that the product has been manufactured safely. Products can be withdrawn from the market if their manufacturer is unable to comply with regulations, but the regulations do not include the terms “clinically proven,” “clinically tested” or “clinically studied”.

Although pseudo-scientific language has been around for decades, post-COVID consumers have developed a particularly strong interest in evidence and “science-backed” claims. In response, brands try to set themselves apart by implying their product meets these new expectations of efficacy. Brands will pay influencers, celebrities, and healthcare practitioners to promote their claims. Sometimes the claims are truly impressive, with the clinical studies to support them. Other times, there is a lot of opacity and science is used to confuse rather than educate.

“Clinically proven” could reference clinical trials that the brand has run for itself, which are then inherently biased. When brands use “clinical trial” frameworks for internal testing, they can develop their own metrics for what “proven” means or for what “clinical” means. Often, the results reference appearance and participant perception in the short-term, rather than function in the long-term.

Exhibit A:

An Indian skincare brand that has conducted “clinical” tests on its moisturiser to show how participants perceive the appearance of their skin after 1-2 weeks of using the product

Brands will use this language of ‘appearance’ and ‘perception’ precisely because they know consumers will conflate immediate surface-level effects with a more studied medical determination.

Exhibit B:

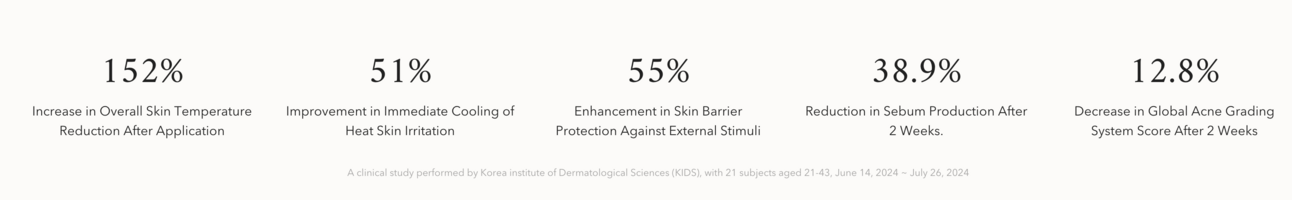

A Korean skincare brand that goes the extra mile and does transparent, third-party testing and publishes detailed results to show how its sunscreen protects skin and has functional benefits over a 45-day period

So what should brands do?

Beauty brands must be more transparent and accountable, without misleading consumers.

For one, they could use terms like “clinically tested/vetted”, “clinically studied” or “dermatologist recommended” in their communications, as that indicates more clearly that the brand has vetted its products to make certain claims. Avoiding authority-indicating terminology like “clinically proven” is key to ensuring that not-so-savvy consumers do not perceive science-y terms as meaning a cosmetic product is a pharmaceutical product because it’s been tested obtusely. This is an important nuance.

Also, in order to know if something is clinically proven, consumers can look up the data. Consumer perception studies are surveys conducted by third-party labs (no measurement or clinical grading), in vitro studies are studies done in test tubes, and in vivo studies are done on humans with clinical grading using experts or machinery.

It’s important to note here that unlike pharmaceuticals, cosmetic brands are under no obligation to publish this kind of data. Visiting the brand’s website and accessing the trial data should be easy to find. If trial data (e.g. photos, graphs, the methods used) are difficult to find, you should be able to contact the brand to get further information. If no further information is forthcoming, it may be that the science doesn’t actually back the claims the brand is making or would not stand up to scrutiny.

It’s not just the language on our beauty product packaging that you need to watch out for. As consumers, we should also be alert to the medicalisation of beauty standards themselves, as it’s often used by brands and even dermatologists as a way to legitimise ideals that are based on aesthetics rather than health and function.

This so-called “science” is often used to promote an ageist, unattainable standard of beauty that is actually scientifically proven to contribute to increased instances of appearance-related anxiety, depression, and dysmorphia.

Just go to any beauty retailer’s website and look for “clinical” or “dermatological skincare”. Some of the “problems” that brands claim to target “clinically” include pores, texture, and wrinkles.

However, pores, texture, and wrinkles are not problems – they are basic human features and come with the territory of being alive. x

★ Stuff I’m currently into ★

If you’re even remotely interested in beauty and the science behind it, I recommend you read this book.

Dr. Michelle Wong’s The Science of Beauty is a refreshing dive into the world of skincare and beauty products, offering an accessible yet scientifically grounded take on what really works and why.

This is also an appreciation post for all the creators out there trying to bring more science (and logic!) to beauty conversations online.

In today’s hyper delulu ‘Instagram/TikTok made me do it’ age, The Science of Beauty tackles misinformation by debunking myths with a touch of humour, and superbly illustrated visuals that enhance the reading experience.

Will eating dairy give me acne? Do I need to wear sunscreen every day? How often should I wash my hair? What's the best way to fade scars? And is "clean beauty" really as healthy as it sounds? The Science of Beauty uncovers the truth behind bold marketing claims and viral social media trends, and tells you what you really need to know about the products you use every day. From the ingredients that make up your make-up, to facts about botox and laser treatments, and whether beauty brands can ever truly be sustainable.

Dr Wong has a PhD in chemistry and backs everything up with evidence. (She also has a superbly informative YouTube channel called Lab Muffin Beauty Science that you should subscribe to.) Her nuanced views encourage you to look beyond the pseudoscience and focus on what the science says about a product’s efficacy.

Whether you’re a seasoned beauty aficionado or a newcomer to the world of serums and sunscreens, this book is honestly such a good read.

That’s it from me this week. See you in the next issue!

xZ

Reply